Angkor, Day 3: Care and Feeding of Stone Temples

It sounds boring, but on the third day, we went and visited temples made of stone. You might say, Peej, that makes it sound much like the first and second days at Angkor. But if there's one thing you should remember about Angkor: they've got a lot of stone temples. They knew what they were good at, and man did they play to their strength.

First up, Phnom Baekang: A beautiful stone temple built at the top of a high hill ("Phnom"= Khmer for "hill")

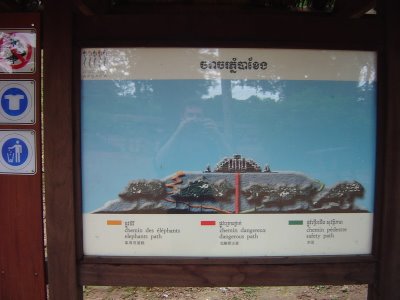

I LOVED this sign at the bottom of the hill. Note the names of the three color-coded paths. Click on the photo to blow it up if you like.

The narrow path with all the elephants on it? Oh, no, that's not the DANGEROUS path. The DANGEROUS path is over there. If you were so silly as to risk it. Me, I'll take my chances right here on this steep, switchbacky slope full of elephants. I'm not stupid. You "thrill seek-ahs" can go over there and tempt fate on the

DANGEROUS path if you wish. Fools.

DANGEROUS path if you wish. Fools.Phnom Baekang is notable for its... (wait for it) Phnom-enal views of other neighboring temples. (I really crack myself up) And for the record, we took the "safety" path.

The path is a good fifteen-minute climb winding around the hill, and completely elephant- and danger-free.

The temple is broad and flat, but the staircase is quite steep. Once you're on top, though, the views are fantastic. I showed you one a couple days ago of me and Angkor Wat in the distance. Here's another one, this time looking south. You can see the mighty Tonle Sap lake in the distance.

Tonle Sap is fascinating: it's Southeast Asia's largest lake... part of the year. The rest of the time it's much smaller. It was one of the principal reasons for the rise of Angkor civilization in the first place- it's a treasure trove of easy protein and fresh water. But how does the size change? I'm glad you asked. The river of the same name (which meets the Mekong at Phnom Penh) runs out of it most of the year, but during the monsoon season (now) the river runs backwards, taking overflow out of the Mekong system and swelling the size of the lake from 2,700 to 16,000 square kilometers. Neat, huh? A few million people live surrounding the lake, and at almost no point is it more than a few meters in depth.

Tonle Sap is fascinating: it's Southeast Asia's largest lake... part of the year. The rest of the time it's much smaller. It was one of the principal reasons for the rise of Angkor civilization in the first place- it's a treasure trove of easy protein and fresh water. But how does the size change? I'm glad you asked. The river of the same name (which meets the Mekong at Phnom Penh) runs out of it most of the year, but during the monsoon season (now) the river runs backwards, taking overflow out of the Mekong system and swelling the size of the lake from 2,700 to 16,000 square kilometers. Neat, huh? A few million people live surrounding the lake, and at almost no point is it more than a few meters in depth.We went and saw several more temples that day, all of which I enjoyed. But to be honest, the heavy hitters all came the day before. At the end of the day, we headed back to Angkor Wat to see it in a different light before we had to go. So rather than talk about the minor temples, I'll take the opportunity to point out some cool stuff about the collection generally.

The photo on the right is not me accidentally taking a picture of my shoelaces. I apologize but I

don't know the name of this small temple near the Baupon, but while climbing down, it occurred to me that one view here illustrates several interesting concepts. Take a look at the red stone just above my right foot. That's laterite, a kind of iron-rich clay that the Khmers discovered was lightweight and easy to dress into blocks of specific shapes, but then dried to a concrete-like hardness after being exposed to air. Most of the great structures at Angkor are made of this stuff. The problem is it's pretty ugly- pockmarked full of Swiss cheese holes. So everywhere they used laterite, it was covered in sandstone or stucco, like the rest of the stones around my feet (which are there for scale). Now, just above and to the left of my left foot you'll see two little round holes. You see these everywhere- they're leftover from the construction of the temple. Wooden poles that held the blocks in place used to fit here. Finally look at my right leg and note that with sufficient exposure to the sun, even my skin can tan to the point where it is noticeably darker than a white sock.

don't know the name of this small temple near the Baupon, but while climbing down, it occurred to me that one view here illustrates several interesting concepts. Take a look at the red stone just above my right foot. That's laterite, a kind of iron-rich clay that the Khmers discovered was lightweight and easy to dress into blocks of specific shapes, but then dried to a concrete-like hardness after being exposed to air. Most of the great structures at Angkor are made of this stuff. The problem is it's pretty ugly- pockmarked full of Swiss cheese holes. So everywhere they used laterite, it was covered in sandstone or stucco, like the rest of the stones around my feet (which are there for scale). Now, just above and to the left of my left foot you'll see two little round holes. You see these everywhere- they're leftover from the construction of the temple. Wooden poles that held the blocks in place used to fit here. Finally look at my right leg and note that with sufficient exposure to the sun, even my skin can tan to the point where it is noticeably darker than a white sock.Renovations

The method/philosophy used at Angkor for preserving the structures is Anastylosis, a technique pioneered by the Greeks and Dutch in the early 20th century (Mark, feel free to correct me). In essence it involves trying to rebuild the structure from the collapsed pieces, replacing components with new material where the originals are unusable or missing. I think it makes sense at Angkor, where you have a lot of the original pieces that have just been knocked down by tree growth.

Here's a great example from Chao Say Tevoda, a small temple currently being renovated by a team of Chinese workers. Normally this temple is closed to the public, but they kindly left the gate open on their day off.

You can easily see the new stonework interspersed with the old.

Here's a close up of new stonework in the process of being dressed down so that it doesn't stand out so much. Very obliging of the Chinese techs to leave their wire brush there for me to photograph, so I can see how the work is being done.

At right, blocks of fresh laterite wait to be brought in to the renovated building:

At right, blocks of fresh laterite wait to be brought in to the renovated building:There's lots of other renovation work, too. The roads often had large earthmoving equipment or gigantic cranes. Many of the temples had one or more wooden buttresses like this one holding up a section of wall.

Also, as Ta Prohm teaches us, defoliation is continual to keep the temples accessible. At first Amy and I couldn't figure out what this incredibly tall scaffold was doing in between three small temples, then we got closer and saw the tree trunk at the center. The branches and limbs had already been removed, but it became clear that felling the tree conventionally wasn't an option: no matter where you had it fall, it would risk damaging a temple. The scaffolding was there to help them disassemble the tree. The squares of latticework here are about four or five feet across; this thing was huge.

Also, as Ta Prohm teaches us, defoliation is continual to keep the temples accessible. At first Amy and I couldn't figure out what this incredibly tall scaffold was doing in between three small temples, then we got closer and saw the tree trunk at the center. The branches and limbs had already been removed, but it became clear that felling the tree conventionally wasn't an option: no matter where you had it fall, it would risk damaging a temple. The scaffolding was there to help them disassemble the tree. The squares of latticework here are about four or five feet across; this thing was huge. After a powerful but brief downpour, we made our way back to Angkor Wat. I lucked out and found a brief moment when no one else was in one of the outer courtyards just before the main spires, and asked Amy to take this shot on the left. The sky was still overcast from the rain, so the light was diffuse* (classic Bernd and Hilla Becher atmospherics) and the stone was reflective and slick.

After a powerful but brief downpour, we made our way back to Angkor Wat. I lucked out and found a brief moment when no one else was in one of the outer courtyards just before the main spires, and asked Amy to take this shot on the left. The sky was still overcast from the rain, so the light was diffuse* (classic Bernd and Hilla Becher atmospherics) and the stone was reflective and slick. When walking around the back of the temple proper, I looked up and saw a tiny patch of green on the northeast spire. Someday soon, somebody's going to have to climb up there and uproot this little tree

When walking around the back of the temple proper, I looked up and saw a tiny patch of green on the northeast spire. Someday soon, somebody's going to have to climb up there and uproot this little treevery, very carefully.

For our third day of roaming around the temples, we had chosen yet another means of transportation. For four dollars one can rent electric bicycles in Seim Reap. They were kind of ugly and awkward to look at, but boy were these things fun! They only went about 20mph (if that) and they were decidedly underpowered when going uphill, but since Angkor is very flat, this wasn't much of a problem. You can pedal them for a little extra oomph, or if your battery goes totally dead, but we didn't exert much effort this way. We spent several hours riding the outer circuit of temples known as the

"Grand Tour", and it made for a lovely pace of travel. The roads between the outer temples were almost all tree-lined and mostly deserted (see picture right). At a dozen sites around the park, there are electric bicycle stations, where your battery can be changed out for free. We recharged twice before riding back to town to catch our plane to Bangkok.

"Grand Tour", and it made for a lovely pace of travel. The roads between the outer temples were almost all tree-lined and mostly deserted (see picture right). At a dozen sites around the park, there are electric bicycle stations, where your battery can be changed out for free. We recharged twice before riding back to town to catch our plane to Bangkok.We spent three days at Angkor, but we met several other travelers who were budgeting as many as seven. After seven days I can see how the temples might start to blur together, but I think if I had it to do over again this is what I might do. I'll have to return to this place. I hope that next time I find it in a healthier and happier Cambodia.

*scroll down in this article to see some awesome shots by my favorite photographers.

1 Comments:

This is great. I love the colors of the temples. Grey and orange. Also the grey and green. I feel some inspiration to do a new kitchen....yes temple colors! The temple eating trees are georgous. Thanks PJ! Neen

Post a Comment

<< Home